Chicken is the blank canvas of the meat world. You might have heard self-proclaimed “foodies” scoff at this kind of scenario before: a person venturing into unfamiliar cuisine tries something exotic, only to declare that “it tastes just like chicken”. Remarkable.

Secret blends and methods of preparation elevate this humble bird to loftier heights. Colonel Harland Sanders of Kentucky has kept his Original Recipe spice blend a secret for decades. On a more local scale, however, Die Henne Wirtshaus in Kreuzberg also shroud the preparation of their ‘house speciality’ in secrecy.

The hush-hush must be borne out of the blank-canvas contradiction. If the alien and intimidating can be flavour-profile matched to chicken, does that mean that chicken—via the right recipe—could be dressed up to taste “just like”, say, alligator?

I’m not sure that Die Henne needs to rely on mystique to get people through the door or to remain unique. Nor would it be too difficult to suss out how they make their half chicken. But this shared piece of lore likely contributes to the community feel of the place. Their chicken…tastes like chicken. In the best way.

The interior of Die Henne has a real beauty: there is a lot of dark wood paired with tasteful dark green accents, in the tiles and coloured glass lanterns which hang from hefty chains, matching the green of the furniture. The bar stretches up to meet the high ceiling before rounding off into an arc, just shy. On display are old barrels of cognac, Glühwein and Grogk; the name of the latter I always feel conjures retching before you’ve even sampled it. There are some trappings of a highland lodge—antlers on the wall, tartan tablecloths—before you are signposted back to Berlin by one of the handsome old ceramic heaters lurking in a corner.

Atop the bar sits an ornate silver cash register which I find myself wanting to hear make a “ding” sound. In reality, they use an electronic system stashed away behind the counter, which embarrasses me when I spot it for having craved the kind of stimulation a toddler needs. Pull the lever to make a sound! Again, again, again! But generally speaking, the place manages to carefully tread the line between feeling like a functioning but gimmicky museum of an old Berlin Wirtshaus and being a genuine relic that has managed to survive.

This authenticity was confirmed by the presence of an elderly gentleman (who I am almost certain was not a paid actor) who sat alone at a table in the corner, surveying the scene. He was later joined by a woman (presumably his wife), who opted to sit next to him, rather than across from him. Seated side by side in harmonic silence—they have likely heard every story the other might have to tell—the pair didn’t eat but enjoyed chain-smoking and watching people drink, dine and make merry. Speaking from experience, Die Henne is as good a spot as any for some people-watching.

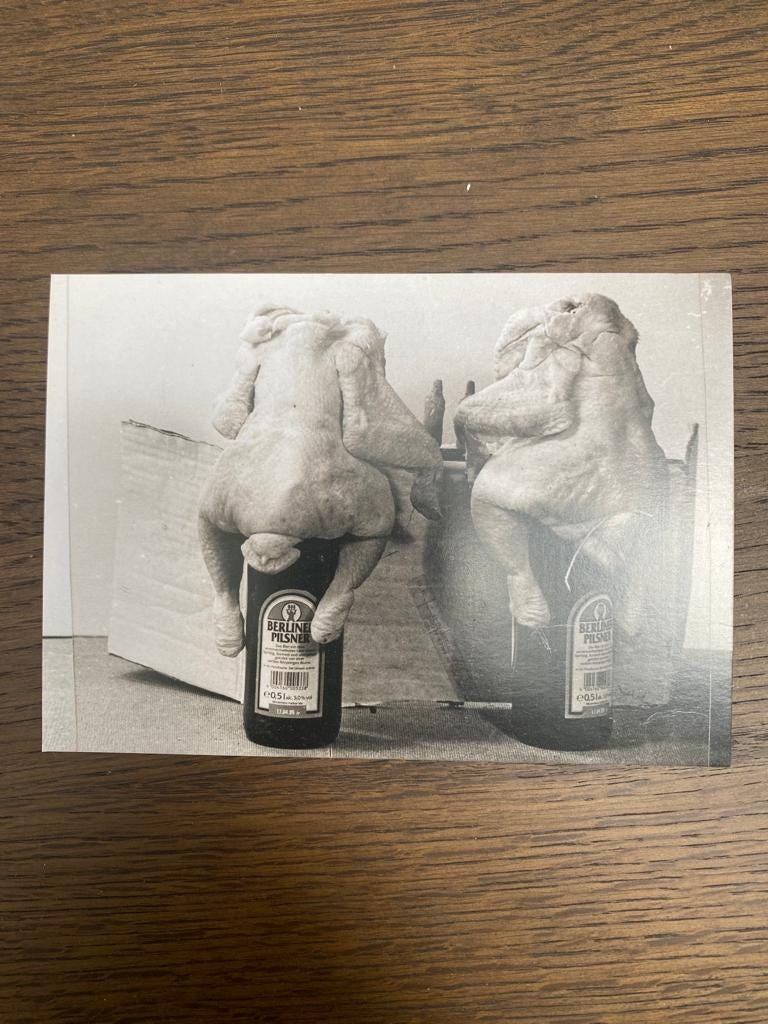

Our group settled in on a long table in the opposite corner. We barely needed to glimpse at the menu: half a chicken with a choice of either Kartoffelsalat or Krautsalat as a side. Both, obviously, please. When the food is delivered to the table, the dish is also served with one singular, regular polygon of bread to mop up the grease. It arrives piping hot and yet you are given only a fork and no knife; you have to tear the still-steaming flesh from the carcass with your hands like a caveman.

The whole thing can be summed up in a word: crispy. Its skin has the kind of all-over, even brown that I strive for on a beach holiday and poking it with a fork created the most satisfying of ASMR sounds. Hot air puffing softly through a papery membrane as it lightly tears and crackles. The bones, too, are exceptionally crispy. I know this because Tobi ate them all and was quite boastful about doing so. I suppose he is being a mindful chef and giving the produce the respect it deserves. I know that, and yet, I still don’t feel I have anything to prove—especially as it might bring him some satisfaction. Spite myself to be contrary, who’s the real loser?

We washed all this down with large Schultheiss beers. Well, a small one for me as I was still hungover at dinnertime having been, the night before, out on the town(!). Dinner was followed by a Pear Schnapps ‘to settle the stomach’ (apparently) and I taught the table about the phrase “kill or cure” when it comes to the-day-after-the-night-before.

It would be a logical enough mistake to think that Die Henne is an establishment named after its prize dish. In fact, the name is more of a happy accident or mark of predestination. Henne was the last name of the original owner, Berndt Henne. The chicken came later as a stroke of ingenuity. Die Henne, in the first instance, was a bar and the half chicken was introduced to line the stomachs of drunken customers so that they could keep on drinking. The fact that the dish is so salty also leaves people wanting to drink more. Intoxicated people at the mercy of their biology are fully catered for, lulled into emptying their wallets.

There are books about the history of the place readily available but we learn this particular origin story from some fellow diners. When having a post-Schnapps cigarette break, we meet a mother and son outside who have just been turned away due to capacity. We invite them to join the end of our table as we have more or less finished up.

When we are all seated inside, I’m struck by how alike mother and son look. She says it is the first time she has ever been turned away and has been coming to Die Henne since its heyday in the 80s. I don’t catch names but I hear that they are from Lübeck and are in town for a concert, which ended up being cancelled. The son is still wearing the band t-shirt though, defiant in his devotion or public in his mourning. Die Henne is on their itinerary every time they visit Berlin.

In the 80s, the Berlin Wall stood right outside. The woman said you could “hit your nose against it” when you walked out of the restaurant. We googled this, being good journalists, and found a picture of the exact spot where Die Henne met the wall—it truly was only a few metres away, this was no exaggeration. She also added that she had no idea that a river ran through Berlin until she saw it for the first time after the wall came down. This claim I am somehow less convinced by but it is a nice enough embellishment.

I can’t fully follow the conversation with these people, I can only snatch at fleeting bits of stories. The woman continues to include me with her eye contact and gestures regardless and I am grateful to her for this act of generosity. Without having to understand much, I can tell she is a born storyteller. She has everyone listening intently and I think I detect a faint pang of jealousy twinge in my back. Tobi is obliging and translates when I ask him to but I don’t want to pull him out of the flow of conversation too often. At points, they will all laugh and I’ll tug at Tobi’s sleeve like a whiny child and ask what the joke was. He will tell me, and it will indeed be funny, but it feels weird and self-conscious to laugh out loud after a delay like the table’s eerie echo. So I chuckle *quietly* to myself instead.

When I zone back into the conversation, the woman is doing a mime show: first sliding one hand over the other and then rubbing her fingertips together in the pay me gesture. Aha, I think, catching myself up to speed, she’s talking about how oily your hands are after eating the chicken; a problem I had also encountered with equal drama. Art imitating my life from 20 minutes earlier. Jonas suggests that this is what the piece of bread is served for; a serviette you eat rather than throw away. Quite a sensible suggestion. Tobi replies with his own mime, slicking invisible chicken juices through his hair like a greasy lothario.

This pantomime gets me thinking once more about how redundant the hush-hush around the chicken recipe is. With Die Henne, it's not how the dish tastes, it's this kind of shared experience. It’s one element in a carefully contrived milieu: a place stubbornly holding onto its past and resisting pressures to regenerate along with the rest of the neighbourhood.

Mainly, because the priorities would be so different. Die Henne is so comforting, it’s almost babyproofed: there are very few options on the menu, the food is perfectly uniform, the beers have just the right amount of froth bubbling over the sturdy glasses. The tablecloths are friggin tartan. It’s almost cartoonish in how simply it presents the thing itself—in its essence—no frills. The nostalgia people are searching out, and that Die Henne clings to, would be impossible to recreate without the history of this place. Even if you had never read a single word about it.

A born-and-bred Berliner (who grew up in Kreuzberg no less) once asked me what my favourite restaurant in Berlin is when wearily making small talk as we folded napkins at the end of a shift together. I panicked at this deeply probing and highly personal question and knee-jerk replied “Die Henne”. He seemed surprised—but on any given day, I might double down on that statement. I often bring visiting friends and family there, not least because it is conveniently located on my road. My housemate Claire and I sometimes talk about things we have stored in our “flavour wank-banks”; Die Henne, our local fave, is filed away in both of ours. Luckily for us, we can indulge whenever the craving calls.